Chapter 13 of The Lean Startup directs attention to the silent drain of human potential and creativity caused by building the wrong things.

Rather than placing blame on upper management or market pressures, it challenges organizations to consider a different approach. The focus shifts from efficiency at all costs to the question of whether something should be built in the first place.

This part of the book argues that much of the waste in modern work is preventable if companies embrace a new mindset and scientific rigor when pursuing innovation.

Recognizing Invisible Waste

The text highlights a persistent issue: the economy appears productive on the surface, but a closer look reveals a shocking amount of invisible waste.

This waste is not defined by physical materials thrown away, but by human effort invested in projects that fail to meet real customer needs.

Traditional management systems often assume projects are inherently risky, markets unpredictable, or employees insufficiently creative. These assumptions lead to an acceptance of failure rates that might actually be avoidable.

Chapter 13 places responsibility on the system, not just the people within it. Past approaches have tried to fix problems by placing blame—on senior executives, on short-sighted investors, or on the broader economic climate.

Yet the book insists that no amount of finger-pointing solves the fundamental challenge: too many organizations work diligently on initiatives that should never have been green-lit.

Instead of celebrating one “brilliant” individual who can see through flawed plans, the chapter urges developing a shared theory that everyone can use to predict and prevent misdirection.

A Century-Old Perspective, Renewed

To drive home the point, the text references Frederick Winslow Taylor’s work from 1911 on scientific management.

Taylor’s ideas revolutionized efficiency in manufacturing, making it possible to produce goods at unprecedented scales.

However, the current era no longer struggles with the question of whether products can be built; it struggles with whether they should be built at all. The problem has shifted from increasing output to selecting the right projects, features, and services that truly address customer demands.

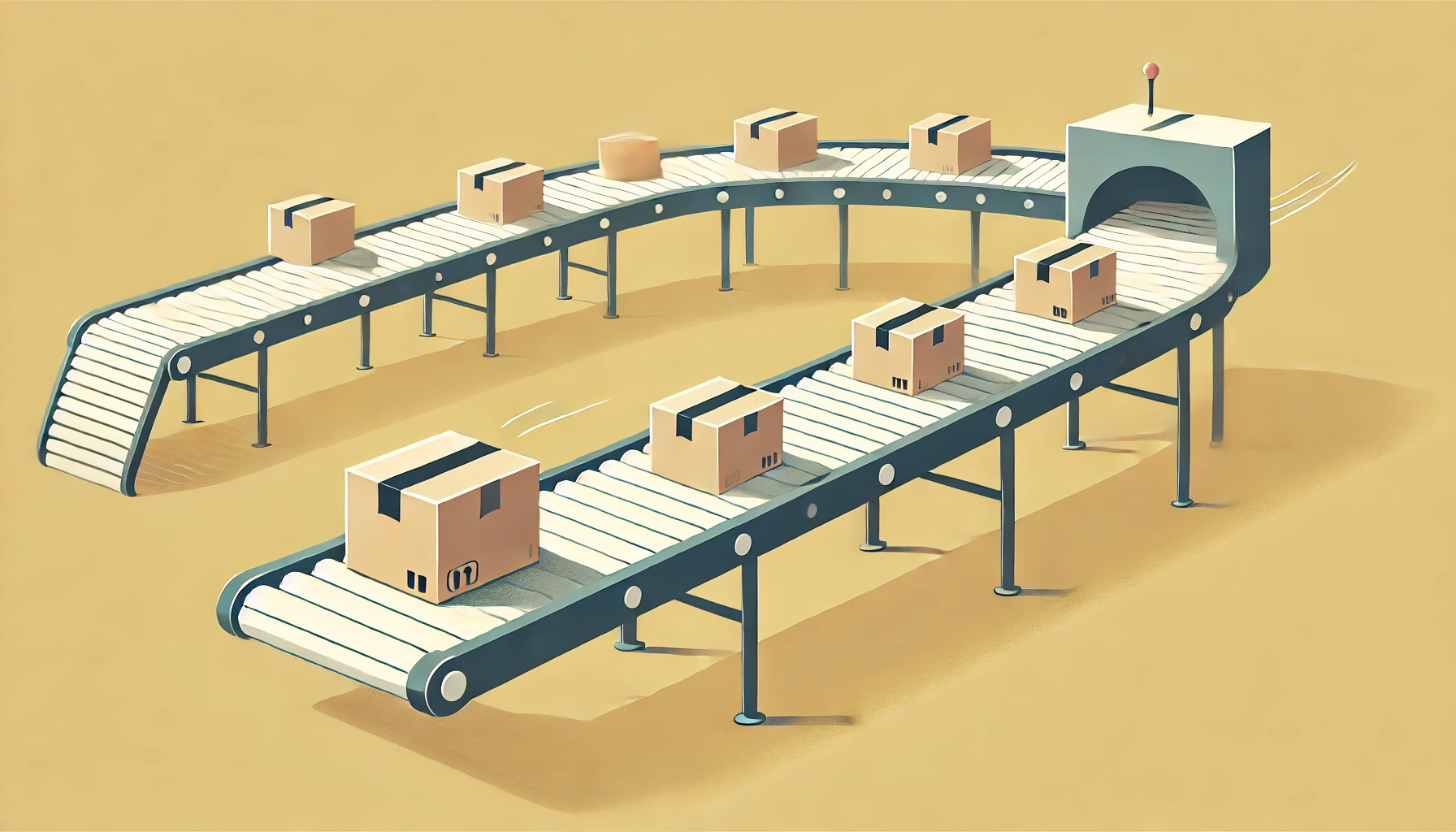

Modern workplaces are already highly organized compared to Taylor’s time, especially in managing tangible materials. Yet invisible forms of waste persist. Ill-conceived product launches, misguided strategic bets, and large-batch development cycles consume vast amounts of time and money.

Chapter 13 suggests that reducing this waste requires an evolution of mindset: a move beyond just making production efficient toward making innovation itself more scientific, hypothesis-driven, and evidence-based.

From Efficiency to Purposeful Learning

Conventional solutions often revolve around working harder or hiring more talented people. According to this chapter, these responses miss the mark. The key lies in questioning deeply held assumptions.

Organizations need to embrace validated learning—using experiments, feedback loops, and actionable metrics to quickly determine if a concept is on track or needs to change direction entirely.

This approach stands in contrast to the old notion that outcomes hinge on heroic leaders or special geniuses. In reality, anyone armed with the Lean Startup methodology gains a framework for spotting flawed plans and proposing well-founded alternatives.

The text emphasizes that the “superpower” isn’t the individual’s innate brilliance; it is the presence of a guiding theory that informs more accurate predictions. Through this lens, success is not about chance or talent alone, but about designing systems that reduce the risk of building unwanted products.

Shifting Beliefs About Innovation

True innovation flourishes when teams apply the scientific method to strategy. They frame assumptions as hypotheses, run controlled experiments, and evaluate results against carefully chosen metrics.

This mentality differs radically from legacy approaches that rely on large up-front investments, extensive market research, and rigid development cycles before discovering whether customers actually care about the offering.

By adopting lean principles, organizations focus on learning what customers value as early as possible.

They can adjust directions before pouring vast resources into a doomed idea. Tools like Teamly’s software (learn more about Teamly here) can foster cross-functional collaboration and continuous improvement, ensuring these learning loops run smoothly.

A Call to Reimagine Productivity

The chapter critiques how modern companies celebrate “efficiency” without questioning the underlying goals. As the author notes, it is pointless to become highly efficient at producing something nobody wants.

Peter Drucker’s observation echoes here: “There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.”

Instead, the goal should be to measure success by the ability to discover genuine customer demand and deliver solutions accordingly.

Organizations that refuse to change remain trapped in a cycle of waste. They celebrate minor improvements in speed or volume while missing that the product itself lacks viability.

By emphasizing that learning is the true unit of progress, Chapter 13 reframes innovation as a systematic, evidence-based process rather than a hit-or-miss endeavor. The path forward involves reducing batch sizes, running meaningful experiments, and using actionable metrics to identify which ideas deserve further investment.

Preventing Needless Loss of Human Potential

The cost of building the wrong product extends beyond wasted materials and lost dollars. It squanders human potential—time, creativity, and energy that could have been spent tackling real problems. The chapter underscores that this is not a minor issue.

When employees pour their hearts into initiatives that fail because the company never validated the concept, morale suffers.

Talented individuals can grow frustrated and disillusioned. The workforce begins to assume that pointless endeavors and failure are normal, reinforcing a vicious cycle of inertia.

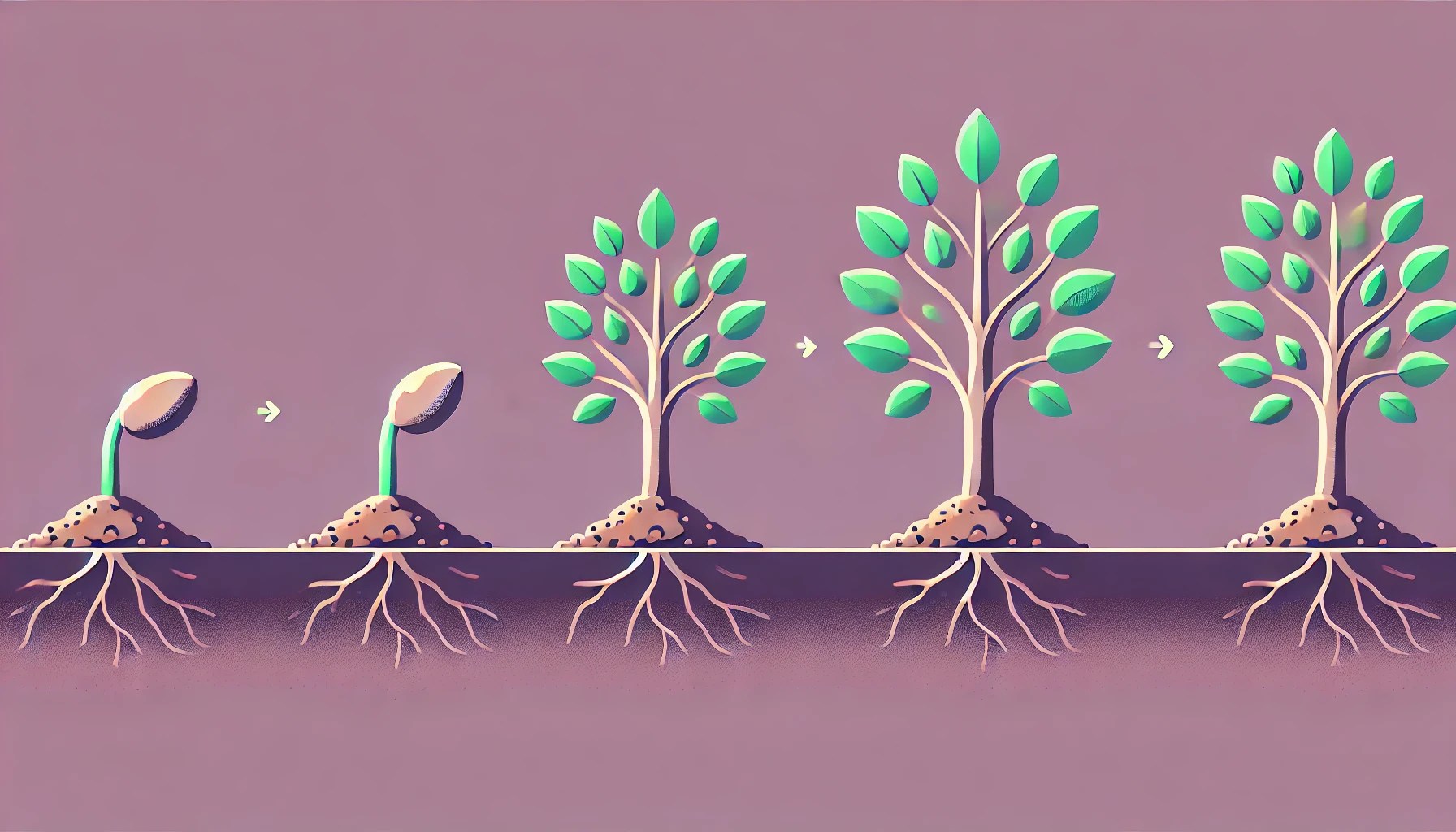

But Chapter 13 offers hope: if companies embrace this new mindset, they can reclaim that potential.

By systematically testing ideas and learning early, they reduce unnecessary failure. Over time, a culture emerges in which everyone—managers, engineers, marketers—becomes adept at questioning assumptions and seeking evidence.

This culture of learning transforms the entire innovation landscape, allowing organizations to pivot, evolve, and stay relevant in fast-changing markets.

A New Era for Innovation

In this new era, the real question is not whether something can be built, but whether it should. The Lean Startup provides a framework for answering that question rigorously.

Organizations that adopt these principles stop wasting talent on initiatives that have no future. Instead, they channel their energies into exploring what truly resonates with customers, paving the way for meaningful, sustainable growth in the long run.

Get your copy of The Lean Startup on Amazon